An article by the University of MN on sweeclover. Good info.

Sweetclover

History

Sweetclover is native to the Bakhara region of Asiatic Russia, and has been used as a green manure and a honey plant for more than 2,000 years. It was first reported growing in North America in Virginia in 1739.

It became recognized for its soil reclamation properties around 1900, when it successfully grew on many depleted, eroded soils of the southern United States.

Acreage planted to sweetclover has declined since usage peaked between 1925 and 1950. Several factors brought about its decline, including:

- A decrease in the use of rotations.

- The prevalence of cheap synthetic fertilizers.

- A potential danger to ruminants from bleeding disease.

- Damage by the sweetclover weevil (Sitona cylindricollis Fahr).

The sweetclover weevil is a dark green snout beetle about 3/16ths of an inch long. Adult weevils consume new seedlings and eat crescent-shaped areas from young leaves. Larvae injure the plant by attacking roots.

Today, a limited amount of sweetclover is grown on Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage. Sweetclover is also commonly found on wasteland and on roadsides, where it regenerates by self-seeding. As the handbook “Forage and Pasture Crops” says, “sweetclover will grow anywhere, provided there is more than 17 inches of well distributed rain, and the soil is not sour.”

Characteristics

The name sweetclover is derived from the sweet odor of its crushed leaves. All sweetclovers contain coumarin, a bitter, stinging-tasting substance with a vanilla-like odor.

Coumarin is indirectly responsible for bleeding disease in livestock. In spoiled and molded sweetclover hay, coumarin transforms to dicoumarol, an anticoagulant. When cattle and sheep consume this spoiled hay, they develop bleeding disease. Horses rarely develop bleeding disease, but can develop colic from moldy hay.

While a cause of death in livestock, dicoumarol and its derivatives have saved many human lives by reducing blood clotting after surgery and the incidence of coronary thrombosis. Dicoumarol derivatives are also used in products like Warfarin for rodent control.

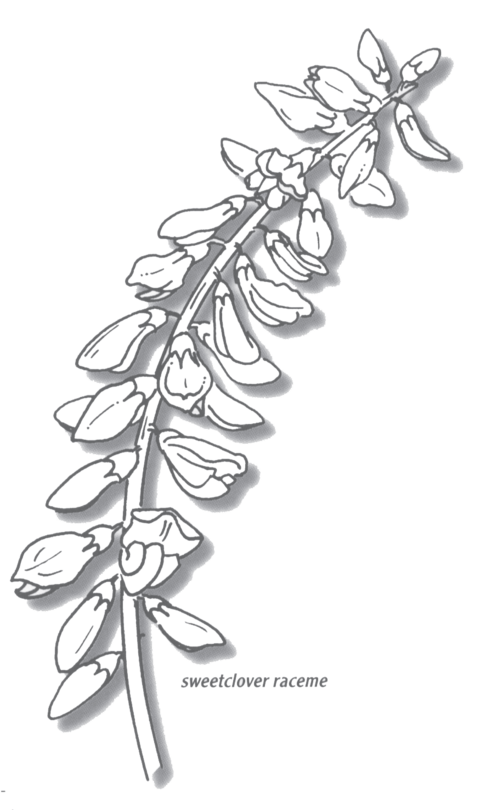

Sweetclover plants are tall, growing to heights of 2 to 4 feet, and have a thick, coarse stem. They produce large quantities of seed that shatters on maturity, leading to natural reseeding. Sweetclover leaves are pinnately compound with serrations around the entire leaf edge.

Most sweetclover varieties, being biennial, flower and die after their second year. There are white and yellow flowered types of sweetclover.

Varieties

Yellow sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis L.) flowers about two weeks earlier than white. The yellow types are smaller and lower-yielding, but also leafier and more drought-tolerant than white sweetclover (Melilotus alba L.).

Over time, a number of sweetclover varieties have been released. However, because of limited demand and on-farm seed production, variety integrity is often lost and seed of specific varieties may not be available.

Most sweetclover that’s found on the landscape usually contains about 2 percent coumarin, but some varieties with lower levels of coumarin have been marketed. Denta is a low-coumarin variety developed in Wisconsin.

In terms of biomass production, yellow and white varieties are similar. Yellow sweetclover makes less top growth in the fall of the first year than white varieties, but yellow increases its biomass yield with greater root growth. White sweetclover (also known as Bakhara, or Bakhara melliot) is taller and has a coarser stem than yellow sweetclover.

Most seed sold is common, however Evergreen (white blossomed) and Madrid (yellow blossomed) are two old-named varieties sometimes available. Hubam is an annual white-blossomed sweetclover variety that’s used as a green manure and emergency hay crop. It yields more forage, but produces less root biomass than the biennial sweetclovers.

Sweetclover seeds. Actual colors may vary with variety and seed lot.

Adaptation

Sweetclover requires nonacid (pH greater than 6.5), reasonably well-drained soils. It’s the legume best adapted to highly alkaline soils. It’s intolerant of poorly drained and flooded soils, but is drought-resistant and winter-hardy.

Use

Soil improvement

Sweetclover is one of the best legumes for soil improvement. It produces high yields of both herbage and root nitrogen, as well as organic matter when not cut. Before the advent of synthetic fertilizers, the Corn Belt routinely used sweetclover as a green manure crop.

When grown for green manure, biennial sweetclover is plowed under in the spring of the second year. Plowing in the spring kills the plants, provided plant growth is at least three inches. In contrast, with fall plowing, plants can regrow in the spring and become weedy.

Honey

Sweetclover is also an excellent source of high-quality honey. It produces an abundance of nectar, and the honey derived from it is light-colored and mild-flavored. One acre of sweetclover is sufficient for one hive of bees.

Harvested forage

Sweetclover isn’t a preferred legume for harvested forage. It’s tall-growing and stemmy, and the forage tends to be low in quality. When cut for hay, you can achieve yields of two to four tons per acre.

The best stage to cut sweetclover for hay is at bud to early blossom. A stubble of 8 to 12 inches is usually left to encourage regrowth. This is because regrowth comes from axillary buds on the stem instead of the crown.

Any cutting of biennial sweetclover the first year reduces root size and vigor the second year. Because of its high moisture content and its rank growth, curing is difficult.

Grazing

Sweetclover is low in palatability because of its coumarin content, and animals tend to eat other vegetation before eating sweetclover. Animals can, however, adjust to it. Sweetclover also causes bloat and scouring, and may taint milk.

Despite these limitations, grazing animals can perform well on sweetclover. Grazing may begin when plants are 14 inches tall, but maintain a minimum height of 8 inches to allow rapid regrowth. Plants become woody and unproductive if allowed to reach bud stage before initiating grazing.