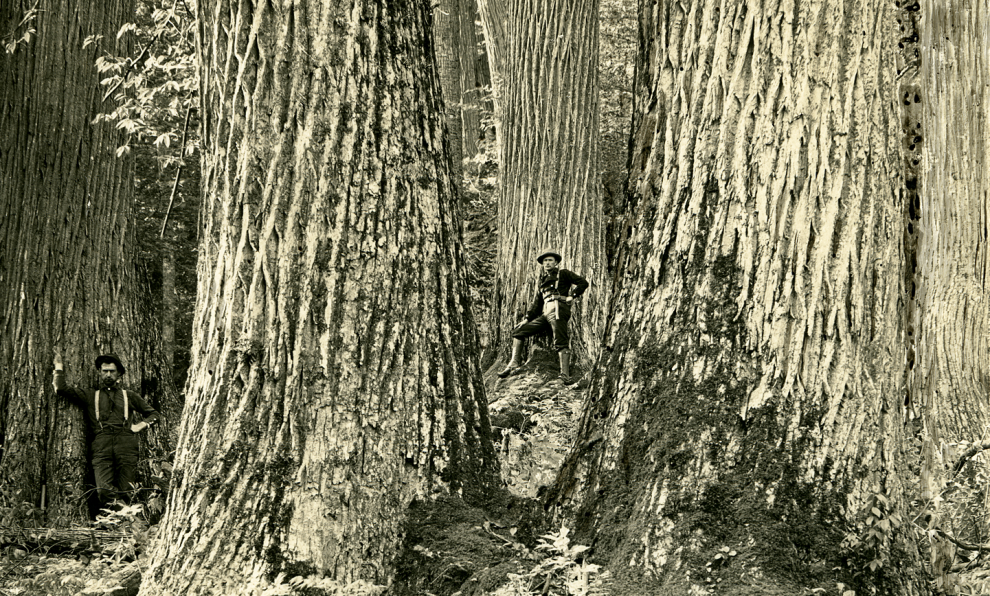

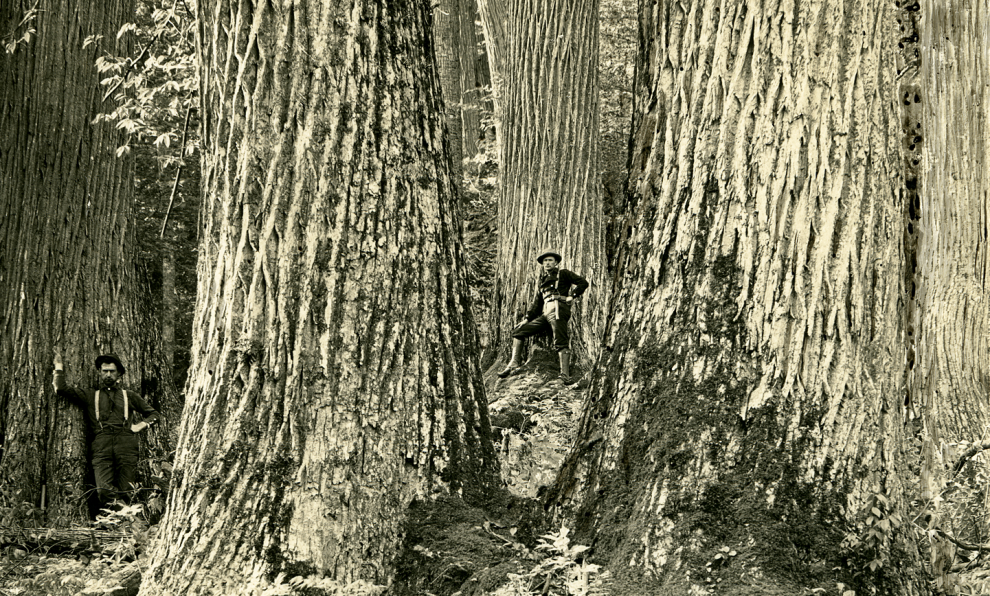

Mind boggling, isn't it? I could not find a source which indicates their age but I am sure they were very old by the time those photos were taken. Apparently the dreaded fungus - Chestnut blight - first appeared in the early 1900s and was announced in 1904. Efforts to develop resistant strains started in the 1930s. The whole thing sort of reminds me of the Irish potato blight which wiped out 1 million (yikes!) people living in Ireland between 1845-1852. The Irish were particularly vulnerable because they were a population with a single food source. That is supposedly a very dangerous state of affairs. The potatoes all rotted in the ground. Such is what makes genetic cloning of plants and animals so risky. With a lack of genetic diversity, one virus can literally wipe out every member of a particular species population in question. We are all here today because our ancestors had the genes to survive all manner of plague and famine. We are the descendants of the people with the genes which enabled them to survive when multitudes of others of their various populations perished. We carry some of those same genes today in our DNA makeup

Here is what wiki says about the chestnuts:

North America

American Indians were eating the American chestnut species, mainly

C. dentata and some others, long before European immigrants introduced their stock to America, and before the arrival of

chestnut blight.

[32] In some places, such as the

Appalachian Mountains, one-quarter of

hardwoods were chestnuts. Mature trees often grew straight and branch-free for 50 feet (15 m), up to 100 feet, averaging up to 5 ft in diameter. For three centuries, most

barns and homes east of the

Mississippi River were made from it.

[45] In 1911, the food book

The Grocer's Encyclopedia noted that a cannery in Holland included in its "vegetables-and-meat" ready-cooked combinations, a "chestnuts and sausages" casserole besides the more classic "beef and onions" and "green peas and veal". This celebrated the chestnut culture that would bring whole villages out in the woods for three weeks each autumn (and keep them busy all winter), and deplored the lack of food diversity in the United States's shop shelves.

[5]

Soon after that, though, the American chestnuts were nearly wiped out by chestnut blight. The discovery of the blight fungus on some Asian chestnut trees planted on

Long Island,

New York, was made public in 1904. Within 40 years, the nearly four billion-strong American chestnut population in North America was devastated;

[46] only a few clumps of trees remained in Michigan, Wisconsin,

California and the

Pacific Northwest.

[32] Due to disease, American chestnut wood almost disappeared from the market for decades, although quantities can still be obtained as

reclaimed lumber.

[47] Today, they only survive as single trees separated from any others (very rare), and as

living stumps, or "stools", with only a few growing enough

shoots to produce seeds shortly before dying. This is just enough to preserve the genetic material used to engineer an American chestnut tree with the minimal necessary genetic input from any of the disease-immune Asiatic species. Efforts started in the 1930s are still ongoing to repopulate the country with these trees, in

Massachusetts[48] and many places elsewhere in the United States.

[46]